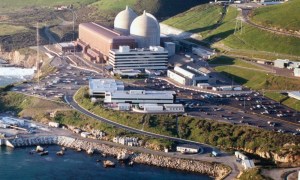

The Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. Courtesy PG&E

The Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. Courtesy PG&E

The California Legislature has just taken the first step toward possibly extending the life of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, the state’s last nuclear facility, past its scheduled closure.

The energy trailer bill negotiated by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration and approved by lawmakers this week allocates a reserve fund of up to $75 million to the state Department of Water Resources to prolong the operation of aging power plants scheduled to close. Diablo Canyon, on the coast near San Luis Obispo, has been preparing to shut down for more than five years.

The funding is part of a contentious bill that aims to address a couple of Newsom’s most pressing concerns — maintaining the reliability of the state’s increasingly strained power grid, and avoiding the politically damaging prospect of brown-outs or blackouts.

Should the Newsom administration choose to extend the life of the nuclear plant, the funding would allow that — although the actual cost to keep the 37-year-old facility owned by Pacific Gas and Electric is not known. Newsom’s office and the Department of Water Resources did not immediately respond to multiple requests for comment. Asked for an estimate, PG&E spokesperson Lynsey Paulo did not provide one.

Even if only a contingency fund, the optics of sending millions of state and federal dollars to the state’s largest utility — which has a recent record of responsibility for deadly wildfires and state “bailouts” — are politically problematic.

In a letter issued to the state Assembly, Newsom announced that he signed the bill, which creates a reserve that he said “will only be used in extreme events such as heatwaves and only as a last resort.”

The governor directed the state’s Energy Commission, Air Resources Board and Department of Water Resources to work with other local, regional and state agencies to ensure clean energy projects are prioritized over fossil fuels.

“The Strategic Reserve will be comprised exclusively of new emergency and temporary generators, new storage systems, clean generation projects, and funding on extension of existing generation operations, if any occur,” Newsom’s statement said. “The bill does not facilitate the renewal or extension of any permit for expiring power plants.”

While it’s true that the energy bill doesn’t itself authorize the extension of the plant’s life, it does provide the money should state leaders decide to do so. Such a move would require “subsequent legislation and review and approval by state, local and federal regulatory entities,” said Lindsay Buckley, a spokesperson for the California Energy Commission.

Overall, the energy trailer bill seeks to address the thorny transition as California tries to move from a reliance on fossil fuels to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. The legislation spells out the state’s concern that, during extreme weather events, renewable energy alone will not be enough to meet the state’s rising power demand.

The state’s solution: Keep Diablo Canyon as open as a failsafe, and pay to retrofit several aging fossil fuel facilities and backup power generation.

“The governor requested this language, not as a decision to move ahead with continuing operation of Diablo Canyon, but to protect the option to do that if a future decision is made,” said state Sen. John Laird, a Democrat from San Luis Obispo.

He also said the public should have a chance to weigh in before a final decision is made on the plant’s fate.

“The shuttering of Diablo Canyon has been years in the making, with hundreds of millions of dollars already committed for decommissioning,” Laird said. “Along with the residents of the Central Coast, I’m eager to see what the governor and federal officials have in mind.”

Located on the state’s Central Coast, Diablo Canyon has been supplying power to the state’s electric grid since 1985. Its 2,240 megawatts of electricity generation is roughly enough to support the needs of more than 3 million people.

In 2016, PG&E announced plans to close the nuclear plant, noting that the transition to renewable energy would make continued operations too costly. The California Public Utilities Commission approved the closure in 2018, after the utility reached a settlement agreement with advocacy groups and environmentalists. The facility has two reactors: One reactor is slated to close in 2024, followed by the second in 2025.

Regardless of the future decision about the lifespan of the nuclear plant, nothing can happen without federal and state funding.

The Biden Administration created a $6 billion Civil Nuclear Credit Program to rescue financially struggling nuclear power plants, and Newsom has said he would consider applying for federal funding to keep Diablo Canyon open past its scheduled 2025 closure.

But in order to access the federal funding, PG&E is facing a July 5 deadline. The utility on Tuesday asked the federal government to grant it a 75-day extension to apply.

Some federal requirements could prevent Diablo Canyon from qualifying for that federal funding, so last month the Newsom administration sent a letter to federal Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm requesting changes to ensure Diablo Canyon’s eligibility. In response, the Energy Department has proposed removing one requirement: that an applicant not recover “more than 50% of its cost from cost-of-service regulation or regulated contracts.”

PG&E expressed support for the change in its own letter to the Energy Department Tuesday. It also urged the agency to give it an extension, adding that it “is needed to provide PG&E the time to collect and analyze the information and prepare an application.”

“The current energy policy of the state is to decommission the plant when the licenses expire in 2024 and 2025, but considering the recent direction from the state, we’ve requested an extension of the application deadline,” Paulo said. “The Department of Energy funding would reduce costs to customers if the state decides it wants to preserve the option to keep the plant open to help with grid reliability.”

But changing the federal rules to accommodate PG&E is a bad idea to longtime critics of nuclear power in California. To keep the plant operating, PG&E would have to seismically retrofit the plant and make heavy investments in cooling system and maintenance upgrades — costs that would outweigh the benefits, the anti-nuclear nonprofit San Luis Obispo Mothers for Peace wrote in a letter sent to the Energy Department on Monday.

Linda Seeley, a San Luis Obispo resident and longtime member of the group, said extending Diablo Canyon will cause a “myriad of problems.”

“This is so ill-advised. It’s a play of desperation,” she said. “I know we’re in a very serious climate crisis, but this is not a rational or practical response.”

Supporters insist the funds are necessary to keep the plant open and advance the state’s goals of getting to a carbon-neutral economy while battling climate change. A coalition of 37 scientists, entrepreneurs and academics on Monday sent a letter to Energy Secretary Granholm expressing support for the Department of Energy’s proposal.

“Considering our climate crisis, failing to pass this amendment could lead to the plant’s closure,” the letter said. “That would not only be irresponsible, the consequences could be catastrophic. We are in a rush to decarbonize and hopefully save our planet from the worsening effects of climate change. We categorically believe that shutting down Diablo Canyon in 2025 is at odds with this goal.”

California is facing steep hurdles in addressing its power supply challenges as the climate crisis intensifies and the state transitions to renewable energy. Soaring temperatures and heat waves have been hitting the state in recent years, straining supply and increasing the risk of power outages. A prolonged drought has depleted hydropower sources, while more frequent wildfires also continue to threaten the state’s electrical infrastructure.

The state’s energy trailer bill, which was negotiated as part of the budget process, significantly expands the authority of the Energy Commission and Department of Water Resources to streamline electric power projects. The bill grants the water agency the authority to site, construct and operate power facilities wherever it wants, and does not require the agency to comply with existing state or local laws.

The bill’s funding could allow PG&E to invest in dry cask storage, a method to safely store spent fuel. The money could also be used for capacity payments — public dollars that are used to sustain a plant’s operations — and to issue flex alerts, when a utility asks its customers to voluntarily reduce their energy consumption and use power during off-peak hours, said Michael Colvin, director of regulatory and legislative affairs at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

The goal, he said, is to have the cash on hand to sustain operations during high-peak hours and potential power crunches brought on by extreme weather.

“Some of that money would be to basically keep those types of power plants around and on standby,” he said. “I look at this allocation as a contingency fund – we don’t necessarily think we’re going to need this but if we do, we want to have some flexibility available. Setting aside some money to be able to do this now is probably a good use of public funds, given the moment that we’re in.”

While Diablo Canyon is seen as a climate-friendly alternative to advocates of nuclear power in California, opponents cite safety threats and problems storing radioactive waste. And the prospect of keeping it open involves numerous technical, financial and logistical challenges. PG&E would need to reapply for licensing with the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which issues the licenses to keep the plant operating, and would need to receive state and federal approval to do so. It would also have to address aging infrastructure problems at the site.

The commission issues operating licenses for nuclear power reactors to operate for up to 40 years, and allows renewal for an additional 20 years at a time.

Though it remains unclear how many more years the plant could be extended, Colvin said it’s unlikely that the state would pursue a lengthy, decades-long extension. He said the plant is more likely to continue operating for another five or so years.

“I don’t think we need an asset like Diablo Canyon for that long of a period of time,” he said, “and certainly not at the size and shape of what Diablo Canyon is.”

CalMatters is a public interest journalism venture committed to explaining how California’s state Capitol works and why it matters.